The Shape of Obviousness

In which an autistic person makes you uncomfortably contend with truth by meticulously deconstructing a silly meme.

Have you seen this meme?

This is, of course, a joke. A mild existential protest. A moment of shared frustration with a subject most people abandoned the moment it stopped being required.

And to be fair, it does make a kind of intuitive sense. It looks like a triangle. It quacks like a triangle. The triangle community isn’t exactly debating its existence. Clearly, it’s a triangle. At a certain point, what else is there to prove?

But here’s the thing: the point of geometric proof was never identification. No one is genuinely confused about whether this shape is in fact a triangle. The exercise isn’t actually about validating what the eye already recognizes—it’s about understanding what makes that recognition meaningful.

A triangle isn’t just a shape; it’s a specific set of relationships. Between sides. Between angles. Between assumptions and outcomes. The goal is to grasp those fundamentals clearly enough that they can be applied elsewhere—to more complex structures, to unfamiliar scenarios, to things that won’t hold if misunderstood. The triangle is just an entry point.

It’s a distinction that probably deserves more attention than it gets. In fact, it’s the kind of thing that could stand to be made explicit when these concepts are first taught. Maybe it is now—I honestly don’t know. I mean, it certainly couldn’t have been when I was in school. Of course, I had more pressing concerns at fourteen than internalizing Mrs. Shaw’s singsong monologue about congruent angles, so maybe I missed it.

But that isn’t the point. I’m not here to reinvent the math curriculum. I’m too busy trying to get people to stop misreading autistic behavior like it’s some kind of personality quiz.

Because the same gap between shape and structure in geometry shows up—often with far more at stake—when society tries to interpret people. Autism is a particularly clear example—not because it’s unique in this respect, but because the mismatch between appearance and underlying structure is so routinely misread.

Most people, when they think about autism, are still working off a kind of visual shorthand subconsciously shaped by decades of deficit-based psychology. Behavior becomes the stand-in for structure. A person avoids eye contact, says something that doesn’t seem relevant, pauses too long before responding, breaks down in public over a seemingly minor inconvenience—and the mental checklist lights up. Triangle.

On the other hand, someone seems fluent, warm, competent, charismatic—and nobody notices a thing.

The assumptions behind those reactions weren’t invented casually. They were formalized. Codified into diagnostic systems that pathologized difference through what could be observed, measured, and controlled. And even as those foundations have been debunked—over and over, both by research and lived experience—the heuristics and the frameworks remain. The stereotypes get updated with friendlier language but remain structurally unchanged. Autism is still something people expect to see in order to believe.

This kind of recognition feels like understanding. But it isn’t. And it’s worth being clear about why. Behavioral presentation can be shaped by so many things—by trauma, by learned masking, by environment, by context, by the degree to which someone has been punished or rewarded for expressing themselves naturally. And yet entire diagnostic systems still treat surface behavior as if it directly maps to internal structure. As if autism is a set of observable symptoms rather than a difference in cognitive architecture.

This is where things begin to break down. Because while the public language around autism has gotten friendlier in tone, the structural assumptions underneath haven’t changed all that much. Deficit-based models are still the foundation. Behavior is still the gateway. If you don’t look like the idea of autism that someone has in their head—often an idea based on clinical stereotypes or pop culture—it doesn’t matter whether the internal structure matches. And if you do look the part, it doesn’t matter whether the assumptions behind that recognition are actually accurate.

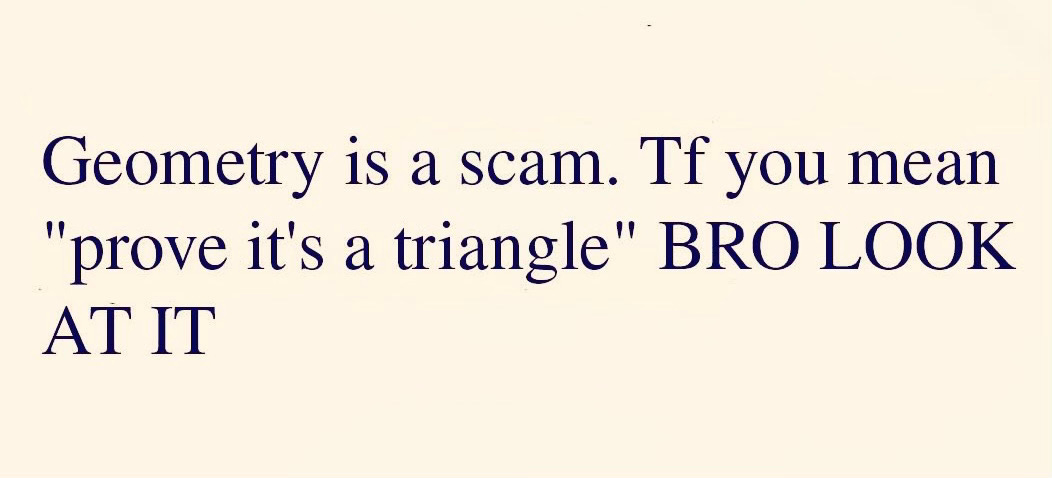

What do you see here?

Is that a triangle?

It looks a bit like one. But no—of course it isn’t.

“Oh, but it could be.” Sure. Obscured by the circle. Maybe it is. Maybe it isn’t.

And maybe it doesn’t matter, if all you’re doing is glancing. But once you start relying on that guess to do anything real—to carry weight, to support something else, to guide how you respond—then yeah, it matters.

Because sometimes the thing you’re looking at is a triangle. But sometimes there’s a hell of a lot more going on beneath the surface.

And in contexts where perception becomes policy—diagnosis, education, care, trust—those surface-level misreads don’t stay contained. They become infrastructure. And when that infrastructure is built on false clarity, everything that rests on it starts to warp.

What’s needed isn’t better recognition. What’s needed is structural understanding. Not just of autism, but of what it means to interpret another human being responsibly. And that requires more than pattern-matching behavior to a checklist. It requires knowing what kind of structure you’re even dealing with. It requires knowing that some people—many people—are operating with a fundamentally different set of cognitive relationships. And that those differences don’t always present in ways you’ve been trained to see.

This isn’t about giving people the benefit of the doubt.

It’s about dismantling the idea that the doubt belongs to you in the first place.

Recognition is not comprehension. Familiarity is not evidence. And obviousness—no matter how confident it feels—is not the same as truth. ∞